Through the Eye of the Needle, Part 3: Acknowledging Affluence and Structural Racism

Editor’s Note: Lay missioner Annemarie Barrett continues the special five-part series, “Through the Eye of the Needle: Unpacking White Privilege in the Journey Towards Racial Reconciliation” on how her time in mission in Latin America is shaping her understanding of racism and privilege.

For much of my life, I was not aware that I was being treated differently as a white person, because most people I knew personally were white, and therefore experienced many of the same privileges that I did.

And I did not realize that the very fact that I was so segregated from people of color and experiences different than my own was part of the structural nature of racism.

As I outlined in last week’s post about white privilege, one aspect of being treated differently are the personal interactions that I experience daily where I, as a white person, am more often praised and valued while my friends and co-workers, who are people of color, are more often criticized or disregarded.

But if I only see racism at play in personal interactions day to day, then I miss the bigger picture.

Racism it not merely personal; it is in fact a structural problem at the societal level, not just locally here in Cochabamba, but also globally, including most cities in the US.

The reality is that being white in Cochabamba not only means that I am treated more kindly, but it also means that I can afford more security, more access to healthy food, safer transportation, cleaner air, and more reliable water access.

SEGREGATION AND ECONOMIC STRATIFICATION TODAY

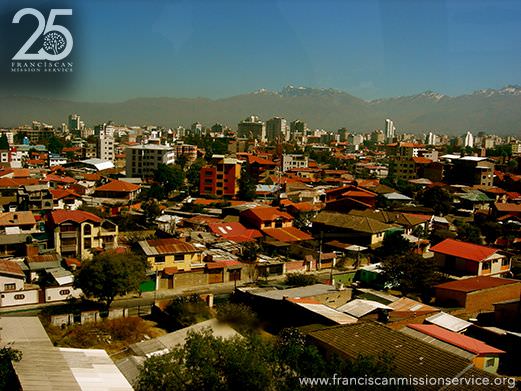

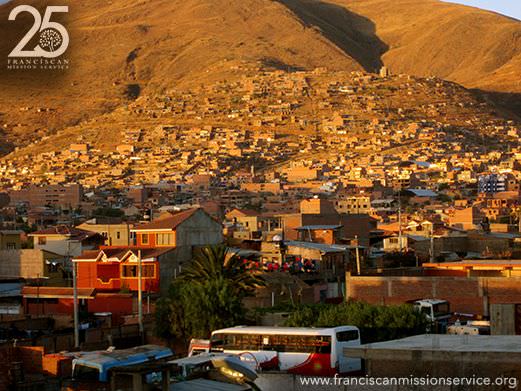

Living in the southern zone of Cochabamba, the most historically marginalized sector of the city and also the historically least white sector of the city, has made me more aware of the reality of structural racism.

Like many cities in the US, including Chicago where I studied before moving here, Cochabamba is highly segregated along racial lines.

In the northern zone, one can see fairly clearly that there are more Bolivians who come from a mixed European descent. The accent in the Spanish spoken is often notably different and many people have lighter skin.

In the southern zone, in contrast, one can see fairly clearly that there is less influence of European lineage. Quechua, one of the 36 state- recognized native languages in Bolivia, is more commonly spoken and the jargon and accent used when speaking Spanish often also sounds notably different. Many people also have darker skin, a reflection of more indigenous ancestry.

And as is typical in many major US cities as well, here there is a direction link between access to basic resources like healthy food, water, sanitation services, security and clean air; and the color of your skin.

Most sectors of the city of Cochabamba have plumbing. But in the neighborhood where fellow missioner Jeff and I live, most families live without plumbing and buy water in barrels week to week. Trash collection is also fairly unreliable and many families burn their own trash as a result, a practice that pollutes the air we breathe every day.

The only organic food market in the city that I know is located in the northern zone, one of the historically more affluent sectors of the city. The largest cable company in the city does not even offer cable TV to the southern zone, although it is offered in all other sectors of the city. Their excuse is that their cables don’t stretch far enough to reach the southern zone, which has been their excuse for going on ten years.

The point is that many basic resources are not accessible to the southern zone of the city like they are in the more affluent zones and that that is not simply a coincidence; it is an example of structural racism. The northern zone of the city is significantly whiter than the southern zone; it also, not coincidentally, has access to water.

An example of the barrels that many families in the southern zone fill with water from trucks that bring water for purchase to their homes.

SYSTEMATIC OPPRESSION OVER GENERATIONS

And the reality is that these systemic injustices have existed for generations and stem from the living history of colonization that started the systematic oppression of indigenous peoples by people of European descent.

The living history of colonization exists in the modern reality of continued systemic oppression of indigenous peoples and people with indigenous ancestry here in Bolivia.

The oppression started with colonization and continues today through unequal access to basic services that contribute to the cycle of poverty. And a very similar living history exists also in the United States.

It is not hard to imagine how a lack of basic necessities like healthy food and water would affect one’s ability to sustain a family or a job. Would your kids be able to learn each day without a healthy breakfast? Would you be able to keep a job or ever seek a promotion if you couldn’t shower more than once a week?

If any person does not have food, shelter, water and regular access to a computer, how can that person expect to find— much less keep — a job today?

And if that person cannot find or keep a job, many people assume that person to be lazy or inadequate. And if more people of color struggle with a lack of access to basic services, then many assume that most people of color are lazy or inadequate. And if most people of color are assumed to be lazy or inadequate then it is that much harder to convince an employer that a person of color is worthy of employment.

It is a vicious cycle that I witness in the communities where I now work, and as I mention in the video below, as a white person, my white privilege exempts me from feeling the burden of structural racism.

RECONCILIATION: GROWING IN HUMILITY, COMMITTING TO SOLIDARITY

And this is why the life of St. Francis of Assisi became so important to me, because he radically modeled one way of unpacking his affluence. Francis radically unpacked his privilege in order to challenge the status quo that fueled the oppression that marginalized communities experienced during his time.

He modeled for us how to relate differently to those most marginalized among us, primarily through humility and solidarity.

And through that humility and investment in solidarity, his example continues to inspire us to relate differently to those among us today who are most marginalized. For those of us who identify as white, his example can challenge how we relate to our sisters and brothers of color.

Instead of assuming that, as a white person, I inherently deserve reliable access to water, we are invited to ask, “Why do so many people of color still live without reliable access to water?”

Instead of assuming that, as a white person, my life is inherently more valuable than others, we are invited to ask, “Why are so many people of color murdered and disposed of like trash?”

Instead of assuming that, as a white person, I am inherently a harder worker, we are invited to ask, “Why are so many people of color breaking their backs doing manual labor for only a fraction of the money I am paid for the work I do?”

Instead of assuming that, as a white person, I am more responsible and equipped to save money, we are invited to ask, “Why, no matter how hard people of color work, are so many still living without any savings account, just trying to break even day to day?”

The answer I have found over and over to these questions is structural racism.

I invite you all to join me next Thursday as I dig deeper into the realities of cultural imperialism and how it affects our relationships and work across race and culture.

Resources and Further Reading (all cited in post above)

- “White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard to Talk to White People About Racism” by Dr. Robin Diangelo, The Good Men Project.

- “CHOLEANDO: Racism in Peru” (video documentary) by Roberto de la Puente

- “What is Systemic Racism?” by Race Forward at the Center for Racial Justice Innovation

- “7 Reasons Why Gentrification Hurts Communities of Color” by Patricia Valoy, Everyday Feminism

- “Chicago’s segregation, seen via time-lapse on the CTA Red Line” by Dan Weissmann, WBEZ91.5

- “5 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Living in a Food Desert” by Ingrid Cruz, Civil Eats

- “Intersectionality isn’t just a win-win; it’s the only way out” by Hénia Belalia, Waging Nonviolence

- “Race Baiting 101” (video) by Matthew Cooke on YouTube

Tagged in: