Through the Eye of the Needle, Part 4: Realities of Cultural Imperialism

Editor’s Note: Lay missioner Annemarie Barrett continues the special five-part series, “Through the Eye of the Needle: Unpacking White Privilege in the Journey Towards Racial Reconciliation” on how her time in mission in Latin America is shaping her understanding of racism and privilege.

I have lost track of the number of times that I have been asked to teach English to someone here in Cochabamba.

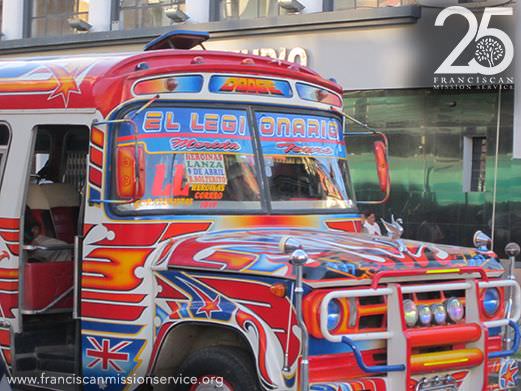

It is normal to be in a micro or trufi (local transportation here in Cochabamba) and be listening to Radio Disney and popular music in English from the US. It is easy to find hamburgers and pizza on any street corner downtown at night. Coca-Cola is available in every store.

Knock-off Hollister and Abercrombie brand shirts and pants are widely available and highly valued by Bolivian teens across the city. And easily half—if not nearly all — of the pirated movies sold at local stands are movies and TV series made in the US, dubbed in Spanish.

This is cultural imperialism. This is the United States, the more economically and politically influential country, exporting its culture to less politically and economically influential country like Bolivia. This is the reality of globalization that is also alive in many other countries beyond Bolivia.

And many people might see the presence of Coca-Cola and Hollister in Bolivia as harmless, even perks for US travelers abroad, the advantage of being a US citizen that can find the comforts of US living available nearly anywhere we travel worldwide.

Some might even see this as progress, a sign that Bolivia, often referred to as a “developing” country is accessing a more advanced version of development and progress that many value in the US.

But what I would like to address in this post is the reality of the marginalization, discrimination, and oppression rooted in racism that are the consequences of cultural imperialism and how our actions as citizens of the US can fuel that injustice if we are not aware.

Cultural Imperialism: Inequality and Injustice

Inequality is the basis of cultural imperialism. By definition, it is the consequence of an unequal relationship between cultures. The United States, arguably the most economically and politically powerful country in the world today, is the more, if not the most, culturally influential country in the world. By default, US culture is thus seen as more merited. In contrast, so-called “developing” countries, like Bolivia, are less culturally influential globally.

This reality influences how I am perceived as a white US citizen living here in Bolivia. I am connected to that economic, political, and cultural power. And that power equates to influence in my relationships here.

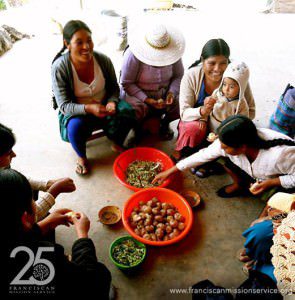

Sharing a meal together in Santa Rosa

The reality of that influence often looks like this:

- In most social situations with anybody but close friends, I am treated differently than the Bolivians around me. I am regularly singled-out, asked about myself, complimented, and asked to be in photos with people I do not even know.

- On home visits in the communities where we work, with women and families that I do not yet know well, I am regularly given a chair to sit on instead of a brick or the floor. The assumption being that the dirt on the floor or a brick would be uncomfortable for me. It is also not uncommon to insist that I use silverware even if everyone else around me would normally use his or her hands to eat.

- People in the local community where I live tell me that they wish they knew English, even though English is almost never spoken in this neighborhood, it is still highly valued and coveted. Many, therefore, also treat me better because I know English.

- When I am invited to participate in cultural dances here by wearing the traditional dress of certain indigenous communities, I am told that I am beautiful and people often ask to take pictures with me.

To me these examples illustrate the normalized inequality in these relationships. By being from white US culture, it is normal for me to be made the center of attention, given more amenities, and treated as superior.

And the shameful reality is that while I am being put in the center of smiling photos for nothing more than being from the US, indigenous people here in Bolivia are fighting for the photos of their repression to be seen and heard even in their own media.

The reality is that while I am praised for speaking English, indigenous languages worldwide are rapidly disappearing as a result of a living history of the destruction of native cultures globally since the beginning of colonization.

The reality is that while I am given special treatment around mealtime, many of the women that work with us maintain side jobs, like peeling potatoes in the large public market for a mere 50 Bolivianos, less than 8 US dollars for an entire day’s work, leaving their hands scarred, scratched and sore.

The reality is that while I am admired for wearing a traditional cultural dress, the women that wear that traditional cultural dress every day are often discriminated against and harassed in public spaces.

And I can tell you that the treatment that I receive is not just basic hospitality; it is not simply interest in me as someone from another culture. It is not the same, because the power dynamic is different.

Choosing humility, mutuality, and solidarity

Sitting together during a house visit in a parish community

I can attest to that difference because I have also experienced a shift in that power dynamic. I have had the privilege of establishing more trust with some of the families that we work with and many friends in the local community where I now live. And in those relationships, trust and mutuality is expressed by not treating me differently than others.

We now share more mutually, I am often given a brick instead of a chair, I am allowed to eat with my hands just like everybody else, I am not asked to translate or speak in English, I am invited to dance together instead of model for photos. These small changes create more trust between us and form friendships. And those friendships invite me to know more about their reality and grow in solidarity.

But that shift has come from long term relationships based on a working definition of trust between us. That shift has come from learning to share traditional food and drink together, honoring the wisdom and history behind the local diet; learning to appreciate local music and dance, not appropriate it; learning to participate in rituals and appreciate indigenous Andean spirituality, not study or commodify it.

That shift has come from me regularly refusing special treatment and learning to share in local ways of being together. That shift has come from countless experiences outside of my comfort zone and norm; it has also come from the profound courage of those in this local community to risk more mutual relationships with me, for which I am eternally grateful and calls me to ongoing conversion through racial reconciliation.

Join me next Thursday as I wrap up this blog series with a final post on the concrete steps I try to take to grow in solidarity.

Resources and Further Reading (all cited in post above)

- “Why are white people expats when the rest of us are immigrants?” by Mawuna Remarque Koutonin, The Guardian

- “Can Bolivia Chart a Sustainable Path Away From Capitalism?” by Chris Williams and Marcela Olivera, Truthout

- “Dignity and Defiance, Stories from Bolivia`s Challenge to Gl” by UChannel via YouTube

- “Schooling the World: The White Man’s Last Burden” (documentary) on YouTube

- “The Disturbing Effect Our Beauty Standards Have on Women Across the World” by Julie Zeilinger, Mic

- “Fotos de represión y asalto a comunidad guaraní en Bolivia” via Territorios en Resistencia

- “Cultural Genocide”: Landmark Report Decries Canada’s Forced Schooling of Indigenous Children” by Democracy Now!

- “The Difference Between Cultural Exchange and Cultural Appropriation” by Jarune Uwujaren, Everyday Feminism

- “6 Ways You Harm Me When You Appropriate Black Culture – And How to Appreciate It Instead” by Maisha Z. Johnson, Everyday Feminsim

- “Imperialism and Ceremony in Bali” by Charles Einsenstein

Tagged in: