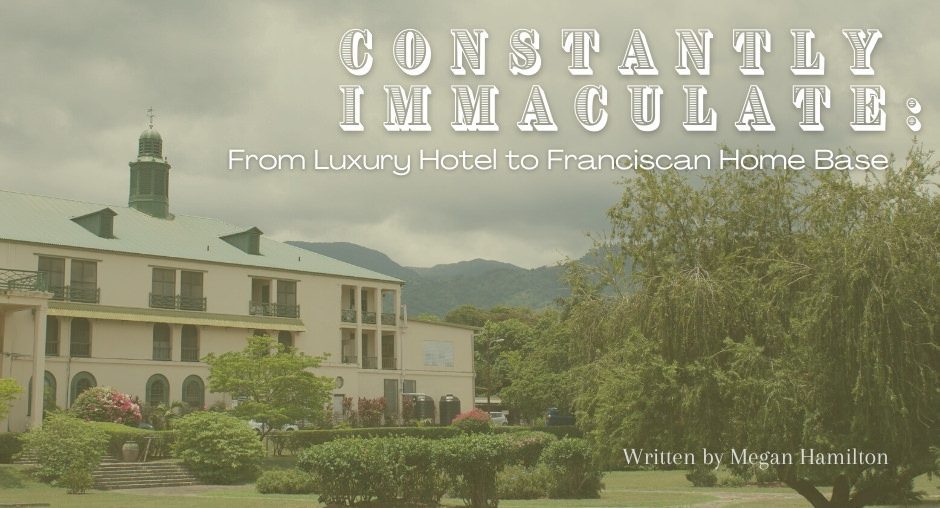

Constantly Immaculate: From Luxury Hotel to Franciscan Home Base

Editor’s Note: Lay Missioner Megan Hamilton delves into the history and Franciscan connections of her daily home-base within the Franciscan Sisters of Allegany convent in Kingston, Jamaica. Megan would like to thank her friend Adrianna Amari who contributed critical research on Constant Spring Hotel.

At my November 16, 2019 Commissioning Mass in Washington DC I swear a vow of “poverty” as a Franciscan missioner. By Ash Wednesday, February 26, 2020 I’m ensconced in a Franciscan convent in Kingston, Jamaica with 24/7 access to a 25-meter pool. Hmmm… would St. Francis approve? Of the pool, I mean?

Which brings up the magical, and I would argue, blessed story of how a scrappy order of Sisters came to own what was once the founding hotel of Jamaican tourism, ultimately turning it into a nuclear reactor of do-goodism. When in full operation it serves as a home-base for educators who founded, managed, taught in nine schools, a retreat center with meeting rooms and a hostel, hosting Peace Corps trainees, 40 medical mission groups a year, and gatherings of people from many faiths. The country club amenities of pool, tennis courts, manicured athletic fields is foundational for a well-rounded education at Immaculate High School, the country’s premiere school for girls, which is open to ANY young woman who has the grades.

The first Constant Spring Hotel opened in 1888, built to house the well-heeled, visiting 1891’s Jamaican International Exhibition. From downtown’s harbor, the electric trolley would pass the private post office before turning into the 165 acres on the Liguanea Plain. The vast, three-story wooden building centered on a 50-foot high stone lobby, boasted the first electricity and indoor plumbing on the island, a nine-hole golf course, and stunning views of the Blue Mountains from lattice shaded balconies. In photos wicker furniture rests on Oriental rugs across polished, wood floors. Servants stand at the ready in pressed whites. The rambling Victorian survived the 1907 earthquake with a fractured stone tower, only to completely burn to the ground in 1927.

Canadian and American businessmen, with interests in steamship routes to the island, bought the acres from the British Colonial government. They commissioned the New York firm of Warren and Wetmore to design their 70,000 square-foot hotel. A busy society firm with Vanderbilt connections, Warren & Wetmore would design over 300 hotels, and become one of two firms to create Manhattan’s Grand Central Station.

Constant Spring Hotel, edition two, was designed to avoid the fate of her predecessor. Her hollow core, cement construction was engineered to flex in earthquakes, the first quake resistant building in the West Indies. Her pale pink arches, cement and tile floors will never burn. Unused to being in a quake zone, I tell my fellow resident Doctor Debra, that I’ve packed an emergency “go” bag just in case. She looks at me in consternation. “Where would you go?” she asks.

The new Constant Spring opened in 1931 in time for the Great Depression. The days of unimaginable wealth powered by the grim business of slaves harvesting sugar were long over. Despite its reputation as “The Golfer’s Hotel” with the additional nine holes added by a Scotch/Canadian course designer, the five-star meals by two French chefs and an Austrian baker, the pool, stables, tennis courts, and option of meeting your porter meet at your steamship, the business failed, coming back to the British Colonial Government in 1940.

Meanwhile downtown the Franciscan Sisters were challenged too. The first three sisters who would pioneer educating thousands upon thousands of youth, arrived from Scotland in 1857 with “two shillings and six pence in their possession”. Luckily the civil in Kingston supported them, and in 1879 the fledgling Franciscan Sisters of the Allegany in upstate New York sent in the cavalry with three more sisters, representing the first American sisters to undertake international missionary work. It wasn’t easy. The 1907 earthquake that damaged Constant Spring ignited a fire destroying their convent and first school. A second fire decimated the rebuilt facility in 1914.

Enter Governor Sir Arthur Richard who had a big building to sell in tough economic times, and LOTS of kids to educate. In 1930 Constant Spring was built for $800,000. He sold it to the Sisters ten years later for $40,000. “Furnished” says Sister Trinita with a gleam in her eye.

Edge of the chapel looking at “my” seat with some flowers from our gardens, natural light and big transom window.

Indeed. In our 100 bedrooms, three dining rooms, tall kitchen, garden courtyard, we are equipped. The lobby with elegant, coffered ceilings has the original moderne armchairs where I envision ghosts of affluent duffers lounging after a day on the links, their cigar smoke wafting round the statue of Saint Francis. When we have cake in the wood paneled bar (now dining room), Sister Colleen puts out the engraved, sterling dessert forks. I wonder…why is the last tine is thicker than the others, and notched to boot? On holy days when wine is served, a few crystal stemware glasses, etched with the CS crest, sneak out with more everyday options.

The island still bears the name, “Xaymaca,” Land of Wood and Water, given by the first Taino people. Much of that forest was Jamaican mahogany, a proud hardwood that transformed the British cabinet making industry. I look at early photos but the slopes behind Constant Spring are already timbered out, as is now the entire country. Maybe that wood came here? I have a mahogany “press”, desk, dresser, night and suitcase stands. Multiplied by a hundred rooms…? My fave steps I call The Mahogany Stairs. They’re barely worn, with one velvety, red, landing board being almost two feet wide. I think of the old-growth mahogany tree, maybe 130-feet tall, that it might have come from.

What I call St. Francis Hall with beautiful arches and the fun, bright tiles that color much of the Convent’s first floor.

My bedroom’s louvered mahogany door reminds me of St. Francis. He loved the outdoors, was forever inviting himself out to tramp God’s kingdom. Our building is forever inviting the kingdom of God in. Summers here the “feels like” temp is pretty standardly 104 with no AC. But this building grabs every breeze that teases its edges, feeding the winds down hallways with dispatch. Opening my louvers that air whips in. With balconies, louvers everywhere, it’s like I live on a ship, windowed “sails” fill with Caribbean trade winds flinging the papery garlic scraps off my kitchen counter.

Our chapel is in the former breakfast room. It reaches into the lawns, surrounded on three sides by French doors topped with huge, arched transoms. I look at the confetti bright tile floors with their curvy splashes of pumpkin orange and forest green. I imagine tinkling crystal, the splash of fresh orange juice, guests discussing their exotic day in the tropics.

At our sunset Masses I sit by open doors. I watch ground doves build a nest in the massive mango tree, pink light gilding the statue of our Lady of Lourdes. Parrots screech that they’re back from lunch in the mountains. The rhythmic, noisy insects join in our singing. Occasionally priests swat a moth from the chalice, mosquitos from their face. At first I feel a bit guilty about being happily, semi-permanently distracted.

But maybe our masses are quite Franciscan! Nature is yelling at us, “Why are you in there? God made this for you! Come play with Him out here!” This a message worthy of a saint who affirmed our fraternity with all creatures, who had the courage to be God’s Fool and preach to the birds.

Like any grand building she has her tales. Above the entrance portico, edging a balcony viewing Kingston Harbor, stands an immense, sheer, white cement cross, a survivor from WWII when religious buildings were marked for protection. At the War’s outbreak Italians were imprisoned in a detention camp on the island. An FSA Sister ministered to them, grateful the Viccino brothers, expert masons who made the cross, a huge doghouse that looks like a stone castle, and (I’m pretty sure) the swan atop the fountain by the pool. It wasn’t there in postcards from before the war!

This statue of Mary in the courtyard was rescued from the original FSA convent downtown during a fire. The brave fireman who saved it risked his life and broke one of his fingers doing so. Fearing he wouldn’t be able to play his beloved violin, the Sisters prayed, his finger recovered, and he played again.

The best story is set to music. The first Constant Spring Hotel was known for its fabulous orchestra, (dancing was an option). The young Scottish violinist Jock Hume performed from Christmas 1910 to April 1911. He’d been playing professionally since he was fifteen. No doubt the gig he and his CS cellist moved on to afterwards sounded super: the maiden voyage of the RMS Titanic.

Years later Christopher Ward researches his grandfather Jock. He finds payment from the Titanic Relief Fund going to his grandmother, but he also finds it going to Ethel McDonald, a dark-skinned barmaid of the Constant Spring Hotel. After her liaison with Jock she’d had a son. Electrified, wondering if he has Caribbean family, Ward comes, digging into the archives. Nothing. Giving up, heading home, he first tours the site where Ethel and Jock met. Hearing the Immaculate High School all-girl orchestra rehearsing he’s invited in, shares remarks, speaking of his fruitless search. Afterward a young musician comes up to him, “My name is Hume, too…” she says, “and your eyes are exactly the same color as my father’s.”

I swim my laps and think of Jock. Was he Franciscan? He for sure found redemption. Somehow he’d let the relief fund know, if not his pregnant Scottish fiancée, that he had family in Kingston, and they were supported with the same amount as his family in Dunleith. Faced with unimaginable tragedy he stayed humane, stayed an artist, and shared his gift when it was needed most. Performing his music in the frigid, horrific dark he comforted. His last song at age 21, was “Nearer, My God, to Thee”.

I do more laps and wonder if I’m Franciscan. If so, I’m a better, happier, more effective one for my time in that water under the fountain with the swan that looks a bit like a goose. The pool may not be poverty exactly, but as my fellow resident Donna says, “It came with the house.”

Tagged in: