Seeds of Progress

I did not miss clean air or water until I did not have access to them.

I did not miss trees, plants, or grass until I could not see them.

And I did not know that my upper class background could buy clean air, access to water, and preservation of nature.

I grew up in the city. But I always had a green lawn, clear air, and lots of trees. We also had unlimited access to water, even lakes within walking distance.

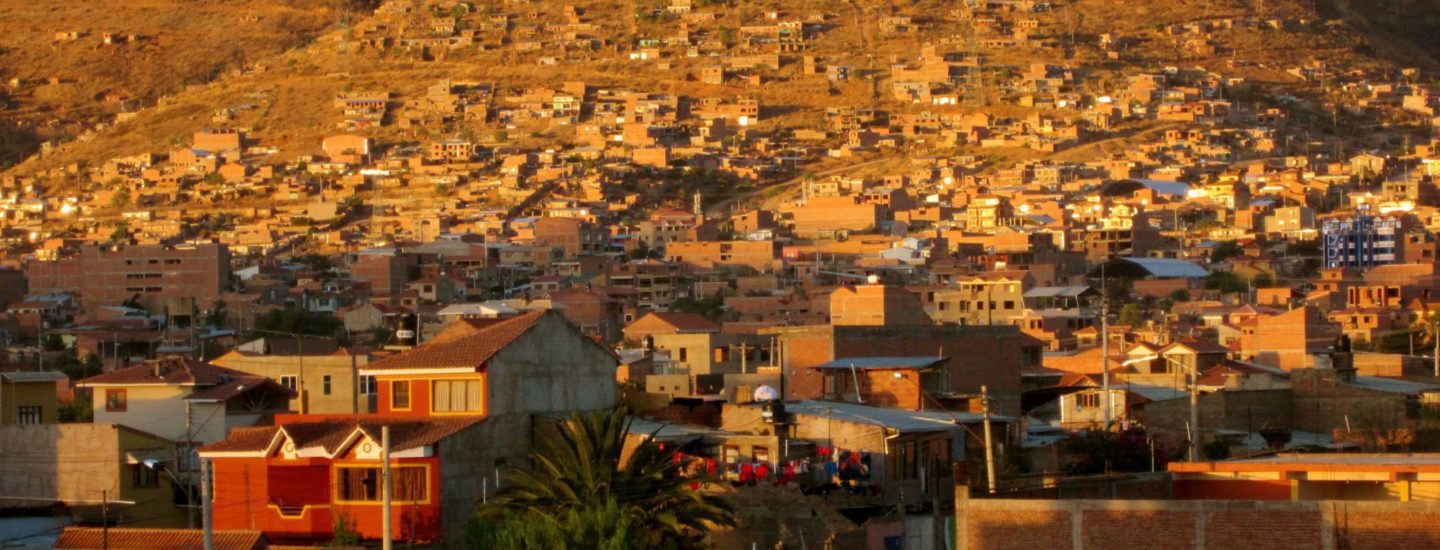

When we first moved to Cochabamba we lived in the northern zone of the city, the notoriously more affluent sector of the city, while we studied Spanish.

The streets were all paved, access to water was in every home, and there were trees and grass filled parks and backyards. Trash collection was also regular and reliable.

We then moved to downtown Cochabamba, in the center of the city, full of concrete. The air was more polluted, yes, but access to water and regular trash collection was regular and reliable.

But there was still a disconnect between where I lived and where I worked.

Then we moved to the southern zone, the notoriously marginalized sector of the city, to an apartment just a few miles away from the parish where I work. I loved exchanging the 45-minute commute from downtown to work for a thirty-minute walk.

But only after months of walking to work did I slowly begin to open my eyes.

I noticed how few trees there were, how little shade I could find from the sun. I missed the grass and the plants. I started really seeing how many piles of burning trash I passed each day and all of the fumes from the trucks and the buses on the major highway that runs through our neighborhood.

I realized that I live blocks away from the largest gas refinery in the city and miles away from the city-wide trash dump, both significant contributors to air pollution in our neighborhood.

And I started to connect the dots. I knew that most of my friends and co-workers in this zone have to buy water in barrels and many do not have plumbing systems. Water is a scarce and expensive resource in this zone of the city. So no wonder there were less public green spaces, there was no water to preserve them.

And burning trash is often practiced in response to unreliable collection services. So no wonder the air I breathed on my walk was so regularly polluted.

And I started to better understand the suffering of the families in the communities where we work and live, almost all of whom have migrated from the campo to the city.

Their motivations for migration are diverse, but the pollution and lack of basic access to resources like water and trash collection are shared in common once they arrive in the city, relegated to a zone with lower property values.

And it is unjust. These are unjust systems that should provide equal access to basic services city wide, but in reality do not.

In the most marginalized sector of the city we do not enjoy reliable access to water and clean air.

And the contrast is particularly stark for migrants from the campo who have left behind clean air and abundant land in the campo for pollution and small land plots in the city. The deep way in which this affects their spirit, rooted in their connection to their communities and the Earth, is a devastating process to witness.

This is precisely why our work in the family gardens is so important. The communities we work with already know how to care for the land, but many believe that they left that way of living behind in the campo. The women we work with know the value of clean air, healthy food for their kids, and green spaces in their homes, but many believe they cannot maintain that life for their families in the city.

Together we are discovering that we can create that life in small ways in the city, through vegetable gardens and harvesting water.

We are learning how to invest in sustainable living that gives life to our families and our communities, practicing both resistance and resilience in the face of Western development and false ideals of progress by returning to the traditional wisdom of this native culture.

Want to be like Annemarie? Apply now!

[button type=”small” color=red url=”/programs/long-term-overseas-mission/”]Become an FMS lay missioner[/button]

Tagged in: